Decision sidesteps anti-dissection rule to insist that trademark components matter

The anti-dissection rule is the cornerstone of any trademark comparison made in India, requiring compared marks to be viewed as a whole, not dissected into individual elements. A unique application of this played a key role in the Delhi High Court’s recent judgment in Bennett, Coleman & Co Ltd v Vnow Technologies Pvt Ltd – a dispute between an Indian media conglomerate and a company operating in the country’s AI development, web design and development spaces (CO (COMM IPD-TM); 117/2021). In its ruling, the court took a calculated detour, weighing the dominant feature shared by the two competing marks rather than relying solely on the anti-dissection rule.

The competing marks

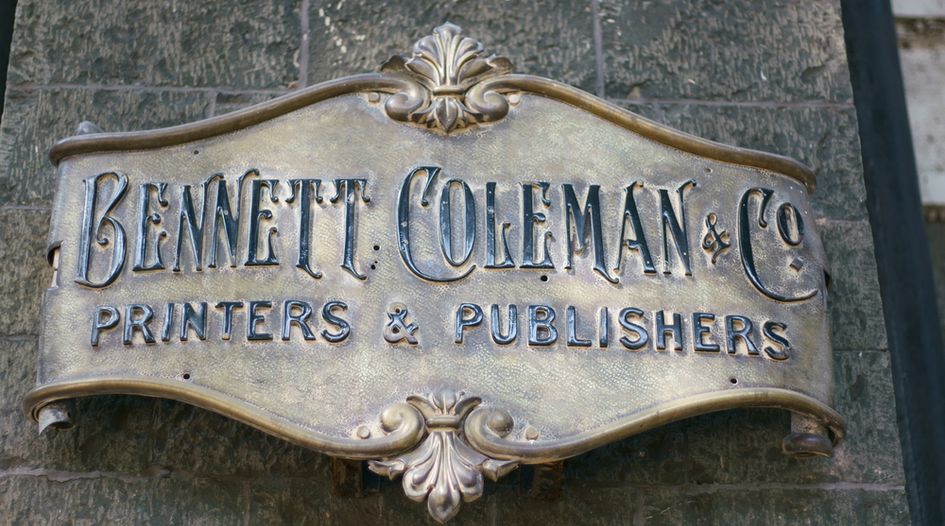

Bennett, Coleman & Co (BCCL) claimed to have adopted the mark NOW as a distinctive and dominant part of its various trademarks, including TIMES NOW, ET NOW, MOVIES NOW, MIRROR NOW and ROMEDY NOW, dating back to 2004, in relation to television, telecommunications and related services. Citing registration and continuous use of its marks, BCCL claimed exclusive rights to use NOW as part of its trademark portfolio. Conversely, the defendants, which included Vnow Technologies, registered the stylised mark VNOW (see Figure 1) in relation to similar services.

Figure 1

This led BCCL to file a rectification petition against the defendant’s mark, contending that the dominant feature – ‘now’ – violated its proprietary rights. Rather than seeking the cancellation of the defendant’s trademark as a whole, the petition specifically asked for the striking off of services that overlapped with BCCL’s interests.

The Delhi High Court’s ruling

In its analysis of the suit, the Delhi High Court studied a selection of its previous judgments, recognising that “proprietorial rights can emerge even from a family of marks held by a registrant, in which part of the marks may be common”. It ruled that the ‘now’-centric TIMES NOW, ET NOW, MOVIES NOW, MIRROR NOW and ROMEDY NOW trademarks constituted a “family of marks”.

The court also referenced Section 17(2) of the Indian Trademark Act, 1999. This provision details the legal principle of anti-dissection, specifying that the registration of a composite mark does not grant exclusive rights to components of the mark – unless they are the subject of separate applications. The rationale for this stipulation is that a composite mark’s impression on consumers is created as a whole, not in parts.

In its judgment, the court deviated from the doctrine of anti-dissection by referring to the decision in South India Beverages Pvt Ltd v General Mills Marketing Inc (2015; 61 PTC 231), in which a division bench of the Delhi High Court affirmed:

The principle of ‘anti dissection’ does not impose an absolute embargo upon the consideration of the constituent elements of a composite mark. The said elements may be viewed as a preliminary step on the way to an ultimate determination of probable customer reaction to the conflicting composites as a whole.

In essence, it deemed that the separate principles of anti-dissection and dominant part were not antithetical but rather complementary to one another.

The Delhi High Court also referred to Autozone, Inc v Tandy Corporation (CO (COMM IPD-TM); 117/2021), which explained the significance of the dominant features of a product’s mark or logo and in which the court held dominant features significant because they “attract attention” and “consumers are more likely to remember and rely on them for purposes of identification of the product”. Conversely, descriptive and generic components were held to have “little or no source identifying significance” and therefore were of “less significance”. These findings collectively established that “words that are arbitrary and distinct possess greater strength and are, thus, accorded greater protection”.

Regarding BCCL’s request for instant rectification, the court was of the view that “where a family of marks is involved, as in the present case, the identification of the dominant part is greatly simplified”. It held ‘now’ to be a distinctive feature common to the company’s marks – TIMES NOW, ET NOW, ROMEDY NOW, MIRROR NOW and MOVIES NOW – and concluded that if a viewer “endowed with the mythical attributes of an average intelligence and an imperfect recollection” were to come across another channel providing similar services, with ‘now’ as a latter part of its title, “there is every likelihood of him regarding the channel as part of the petitioner’s repertoire, or at least as having an association with the NOW family of channels of the petitioner”. Consequently, the Delhi High Court allowed the rectification petition and ordered a suitable modification of the specification covered under the respondent’s stylised mark VNOW.

The case’s impact

The Delhi High Court’s application of the anti-dissection and dominant feature principles with regard to the comparison of trademarks in makes this a potentially influential case.

If courts follow the decision’s lead in future judgments, rights holders – especially those that own a family of similar marks sharing a common feature – could benefit significantly. However, it will be fascinating to see how this is weighed against a ‘crowded field’ defence, in which an alleged dominant feature appears in several marks found in the trademark register.

This is an Insight article, written by a selected partner as part of WTR's co-published content. Read more on Insight

Copyright © Law Business ResearchCompany Number: 03281866 VAT: GB 160 7529 10