Evolving online route-to-market strategies and how to combat them

This is an Insight article, written by a selected partner as part of WTR's co-published content. Read more on Insight

The evolution of the digital market and online counterfeiting

The online marketplace has made distributing products and services more efficient, exponentially increasing business transactions globally. It has become the cornerstone of supply to the end consumer.

While the continuous evolution of information technologies and the multiplication of e-commerce platforms have significantly increased the distribution channels of individual companies and redefined the concept of territoriality, they have also created new cases of infringement and counterfeiting of IP titles of ownership of international brands.

The online marketplace has allowed the counterfeit industry to increase its production chain, threatening and limiting authorised distribution channels. This phenomenon, which does not only affect the fashion, luxury goods and digitised intellectual works sectors, produces great damage both for rights holders and for the safety of the end consumer (think, for example, of the sale of products such as drugs and spare parts that do not comply with the quality standards and certifications provided at the European and international level).

The advent of Web 3.0 (also known as the Metaverse), the spread of NFTs and the widespread use of AI have allowed users themselves to directly produce and make works and products (digital and otherwise), further jeopardising the proprietary rights of companies.

No less important, social networks have revolutionised users’ use of the web, significantly influencing their habits of purchasing and disseminating content while at the same time generating new instances of infringement and misuse of others’ rights in the digital world. This has given rise to new terms and professional figures who play a primary role in online business dynamics. For examples, think only of the fake news (and the reputational damage it causes), violations of copyright and other illicit activities conducted by influencers and bloggers.

Counterfeiting and piracy represent major challenges in today's innovation-driven global economy. Intellectual property generates value for businesses and economies, and the effective protection and enforcement of IP rights, in general, helps promote innovation and economic growth in states.[1]

Illegal practices such as piracy and counterfeiting generate negative effects on the sales and profits of the companies involved, as well as negative economic, health and safety consequences for governments, businesses and consumers. Moreover, it has been observed that organised crime groups play an increasingly important role in these activities, benefiting significantly from these profitable operations.

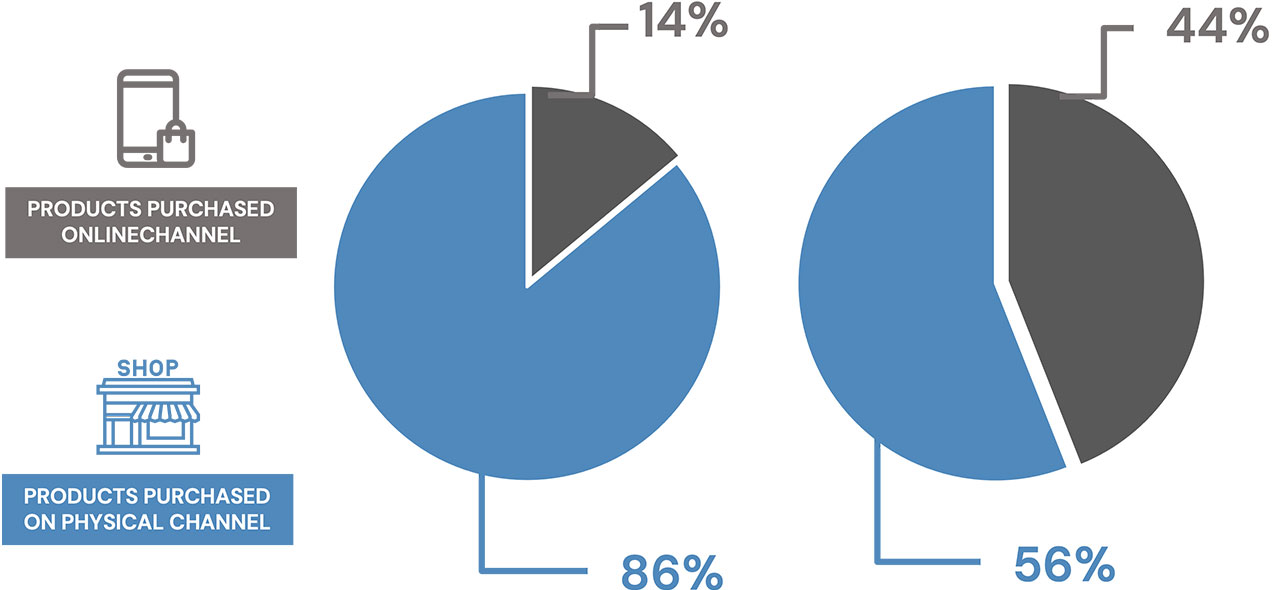

As noted in the FATA project, a recent report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)[2] and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) on the trafficking of counterfeit goods related to e-commerce purchases, based on seizures conducted by customs authorities in EU member states, shows that 56% of counterfeit goods seized in the European Union in 2017–2019 were attributable to products sold online. However, in terms of economic value, only 14% of counterfeit goods were attributable to online channels. This is also compounded by the fact that 11% of the conversations identified on social networks that concern physical products refer to ‘fake’ items.

Distribution of value and number of seizures of counterfeit products purchased online and on physical channels

The new strategies adopted by ‘bad actors’

Counterfeiters use various online channels in an interconnected manner, both to advertise and sell counterfeit products, and to commit other crimes at the same time. Among the main channels that FATA’s research has delved into are: social networks; fraudulent sites (eg, clone sites made through cybersquatting – that is, the speculative registration of an Internet domain name corresponding to someone else’s brand name or that of a famous person – and/or typo-squatting, a form of cybercrime in which hackers register domains with deliberately misspelt names of known websites); marketplaces; instant messaging applications; web-forums and chats (eg, video game chats).

© Ministero dell’Interno and Crime&tech-Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 2022

When actors with rather ambiguous aims, such as organised crime groups who have brokers or influencers on their side, act on the aforementioned channels, the conditions are created for the emergence of a criminal ecosystem, characterised by multiple interconnected digital crimes (fraudster journey). The FATA study describes these as follows:

- sale of 'fakes,' through the channels and methods outlined above;

- identity theft of consumers and sellers, including payment method data, such as through e-skimming techniques (a hacking technique that steals information uploaded by customers on online shopping sites) on 'clone' sites or phishing (a social engineering attack that aims to make users believe that the email they receive is from a trusted institution);

- dissemination of malicious software through fraudulent marketplaces or clone sites, and always aimed at identity theft or extortion purposes (ransomware);

- fraud in payment services, using stolen identifiers or previously cloned cards; and

- fraudulent returns, following online purchases, involving, for example, the return of counterfeit versions instead of the original products.

That being said, it is appropriate to examine individually some current illicit practices, or those that have evolved most over the years, which, through the detour of web traffic by means of direct and/or indirect hyperlinks to the navigation page, aim to damage and/or infringe the rights of intellectual property rights holders – for example spamming, linking, framing and meta-tagging.

Spamming is defined as the practice of sending the same message to a large number of users at the same time, via either email or newsgroup. Regardless of its content, the message will be considered spam if it is sent to a plurality of subjects and if it has not been solicited by the recipients.

With regard to the issue at hand, it should be noted that spamming takes on a certain significance in the context of marketing counterfeit goods. Moreover, such activities not only advertise fake products but often cause detriment to the trade name and prestige of the company that is the victim of such offenses.[3]

Linking is the use of hyperlinks from one web page to another. It can take one of two forms: (1) surface linking, which occurs when the link is set up to allow linking from the source site to the homepage of the target site; and (2) deep linking, which occurs when the link transfers the user from the source site directly to the interior of the linked site. These activities are not illegal in themselves, although the use of someone else’s trademark in a link will only be permitted for the purpose of referring to the site of the trademark owner and/or to indicate the Internet sites where it is possible to purchase products with that particular trademark, placed on the market directly by the owner and/or with the consent of the latter, without any likelihood of confusion arising from this.

Framing is a special form of linking through which the user, upon first accessing a web page, will be given access to a second page outside the first site. However, unlike in linking, the called-up web page will be displayed within the frame of the first site, so that users will continue to view the advertisements on the same page.

Meta-tags are special HTML tags used by search engine software to index web pages. They are invisible to users in the final layout of the web page being consulted. However, they can be extracted by viewing the site’s HTML source code.

Among the illicit conducts that have emerged in recent years and are most widely used by counterfeiters, the following also deserve mention:

- Drop shipping: this is a business model characterised by the presence of a retailer who does not physically hold the product but rather buys it from a third party (the drop shipper), directly shipping it only upon receipt of the order from the user. The ‘digital’ nature of such a business model and the speed with which fake websites and social profiles can now be created, has allowed the counterfeit industry to set up various scams and frauds, and to create distribution channels for counterfeit products. Drop shipping gives counterfeiters numerous economic advantages and faster sales timelines, since they do not need sophisticated logistics strategies, nor have to engage in the assembly, production or packaging of goods. This makes it complicated to track and crack down on their illicit activities.

- Fast fashion: this is also a widely used business model, especially by some of the major brands in the luxury fashion sector. It is concerned with optimising supply chains due to seasonal fashion trends, producing product lines quickly and economically and enabling the end user to purchase products at lower prices. Although this strategy originated in the mid-2000s, the last five years have seen an increasing use of it even by some of the leading online platforms (among which Temu and Shein deserve mention). These have achieved important results – both in terms of turnover and territorial expansion – bringing this business system to a higher level that is today referred to as ‘turbo-fashion’. It is quite clear, for the reasons highlighted above around drop shipping, that this business model is also widely used by the fake industry, due to the optimisation of production costs (of fake garments) and the limited time frame that characterises the sale of products.

- Dupe economy: a further and recent phenomenon of physical and digital commerce (created as an evolution of the business models just examined) is so-called dupe culture. This leveraging younger generations, who love to flaunt symbols of luxury (clothes, perfumes, accessories and cosmetics) and – with the help of social media and influencers – market products that emulate the style, color and packaging of their originals. This strategy echoes the dynamics employed in the past for ‘copyright fakes’ (or ‘equivalencies’) but is more persuasive since it is put in place, in most cases, by well-known influencers who make a comparison to the original product and/or refer explicitly to the distinctive signs that identify the latter. While this practice is not in itself illegal, it is used by the counterfeit industry to devise items that present similar but different visual elements (in terms of product and packaging) from the original product.

The counterfeit industry is constantly updating with respect to these developments and commercial dynamics. At the same time, it has full knowledge of the gaps in national and supranational regulations, as well as their non-uniformity. It is also able to circumvent the policies of most IP rights protection platforms present in the main online marketplaces. In addition, counterfeiters make precise choices in terms of distribution strategy and defining the individual digital content to be put online, attempting to circumvent the control and monitoring technologies used by brands and/or offered by third parties in the field of online brand protection.

The availability of technology and the large number of digital platforms currently present online allows counterfeiters to carry out real misdirection initiatives, enabling them to conceal the real production site and the main distribution channels used. The result is that, although the monitoring and takedown initiatives performed by brands (or those on their behalf) allow some critical online issues to be removed, these represent merely the tip of the iceberg in terms of of the criminal organisation, which accepts such removals as they are arranged ad hoc to deflect the online protection investigations performed by IP rights holders.

A lack of uniformity between the policies provided by individual online platforms and between legal systems, as well as knowledge of the infringement monitoring and detection software currently used by brands, allows the counterfeit industry to devise specific content that can circumvent such protection tools or direct them to their liking. This content can then be published on platforms on which the owner does not boast any IP title to act, or at least does not possess all the types of registrations provided for that individual platform.

In light of the above considerations and because of the constant technological development, the counterfeit industry should probably no longer be combated on a large scale – through the blackout of numerous, but disconnected, online sales listings, for example. Instead, a targeted and circumscribed strategy should be put in place, using the instrumentation offered by online brand protection, in order to prepare an enforcement and anti-counterfeiting strategy that can target the actual production site.

The advent of new technologies and new frontiers in the fight against counterfeiting

The rapid technological evolution of the last decade has presented new challenges to intellectual property, posing different interpretative and enforcement issues that respond to the protection and definition needs of the new digital scenarios.

This was recently addressed by the EUIPO, in its drafting of the Intellectual Property Infringement and Enforcement Tech Discussion Paper 2023.[4] This addressed the potential implications and repercussions of the new technological realities on intellectual property rights.

Among some of the new scenarios to have emerged, mention must be made of artificial intelligence, which Section 27.3.1 of the paper addresses in relation to copyright. The use of AI has given rise to several innovations that directly impact the legal system and intellectual property, among which ChatGPT deserves mention for the media attention it has received.

Generative artificial intelligence has created important professional opportunities and, at the same time, has caused new regulatory gaps. These have required the intervention of the European Legislator, materialised in the so-called AI Act.[5]

Among the critical issues that arise as a result of the use of a ‘generative AI’ system are those inherent in intellectual property rights, both in terms of input[6] (in the implementation phase of the AI model, and output, that is, because of the work created through such technology.

Among the scenarios that intellectual property will continue to encounter, two digital trends that have characterised the last two years and that create several interpretative issues from a legal point of view deserve mention: the Metaverse and NFTs.

With the advent of the Metaverse and the creation of ad hoc platforms for the sale of NFTs, several fashion and non-fashion brands have implemented targeted marketing strategies, devising digital product collections. As was the case with the rapid spread of Internet 2.0 (which led consumers to make daily use of the numerous online marketplaces and e-commerce), some critical issues regarding counterfeiting and IP title infringement emerged immediately.

As examined above, the fake industry can make the best use of new technologies that develop over the years. One high-profile example is that involving the Japanese fashion house Uniqlo and the Chinese fast-fashion company Shein, before the Tokyo Court. The latter allegedly made use of an artificial intelligence algorithm capable of monitoring market trends and, consequently, putting in place the targeted production of replica products (‘dupes’) that significantly limited the authorised distribution channels of its Japanese counterpart.

Another phenomenon widely used by the counterfeit industry is the sale of non-genuine product through some influencers on major social media platforms (‘dupe influencers’), who knowingly or not promote counterfeit products or cheap replicas of original products that belong to major international brands.

Such ‘commercial and advertising practice’ can also have negative repercussions in terms of brand reputation, since such individuals (nowadays also artificially created through the help of artificial intelligence) also influence the market and end-user choices through the publication of fake news or false reviews.

As analysed in this chapter, the digital revolution, understood as a radical transformation of the social and economic structure of civil society, can no longer be defined and regulated on the basis of the traditional principles that have hitherto characterised and regulated the various legal institutions (person, civil liability, property, and business). The hope is that the new regulatory proposals, including the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the AI Act, can, with the help of previous and current European and international law, regulate all the new digital realities, provide the necessary tools to protect rights even in such parallel realities, strengthen the accountability and transparency of digital platforms, and anticipate and counter the spread of illegal content.

A personal look into the current loopholes in the European legal system, in the area of the online counterfeiting

Although big changes have been made in recent years to raise awareness in the field of intellectual property protection, there are currently some discrepancies between large brands and small-to-medium-sized companies that do not arise exclusively from economic issues and the allocation of certain resources to the fight against counterfeiting.

The current scenario allows companies to make different approaches in managing the fight against counterfeiting and online brand protection. Some large international business entities have created an ad hoc department at the corporate level, to which they entrust the task of intellectual property protection and prevention activity (with the help of subordinates responsible for the anti-counterfeiting activity in specific geographic areas or individual countries, in the case of corporate entities with multiple locations and/or business interests worldwide). Such brand protection managers cooperate with internal Intellectual Property and Legal Affairs departments to define anti-counterfeiting strategies, such as managing allocated budget; managing company assets; coordinating with any third-party figures and/or competent authorities for enforcement and monitoring of the real and virtual market; and managing and registering trademarks, designs, patents and domains.

Meanwhile, other companies (or senior figures within them) believe that there may be positive effects to counterfeiting. These companies assume, usually erroneously, that the presence of a counterfeit product indicates a certain level of notoriety and trendiness, and that this phenomenon can even be connoted as a free tool of publicity and dissemination/dissemination at the international level of corporate products/services. This hypothesis is especially true of ‘young’ brands, which could exploit, according to the opinion under consideration and not shared, the media resonance of such non-genuine products through their exponential diffusion on international social media.

Such a position can also be found among some internationally renowned luxury brands, which surprisingly believe that a counterfeit product increases the perception of exclusivity of the genuine product, consequently raising the level of desire and adulation among consumers. These brands fail to understand (or deliberately avoiding doing so, for economic reasons) the seriousness of the negative consequences associated with the marketing of non-genuine products in social, economic and health terms (as well as to the image and reputation of the brands themselves).

That being said, the exponential development of the digital market, the criticality of the protection tools in the field of intellectual property and the total inefficiency of certain intervention strategies (especially in the field of online brand protection) in certain territorial areas have all increased significantly. They bring to light several critical points in the overall system of online market protection, as well as its fragmentary nature.

Although discrepancies exist at the level of individual countries, due to the diversity of individual national legislations, it is believed that a great opportunity to remodel the legal system of protection of IP rights has been missed. This is encouraged by recent jurisprudential pronouncements and regulatory productions, among which the DSA and the Digital Markets Act (DMA) deserve mention. Such a remodelling would offer more incisive and effective tools to fight counterfeiting, starting precisely from the digital market, which is the main distribution channel for counterfeit products.

It is probable that the intent to equate the online market with the real market, in terms of the identification of infringements and their punishability, has led legislators to issue regulatory provisions that do not substantially deviate from the provisions of the previous legislation (eg, ‘E-commerce’ Directive 2000/31) and lose sight of the real connotations and peculiarities that differentiate the virtual market from the real market.

The transposition of some legal principles from the real market to the online market has led to the emergence of several conflicts between different jurisdictions involved in individual cases, as well as a limited interpretation and implementation of the concept of territoriality in the digital market. This has caused a profound crisis of this principle, since digital crimes are often characterised by their extraterritoriality, which underlines the obvious diversity and absolute non-uniformity of the protection regulations and the protection tools offered directly by the subjects (eg, ISPs) involved in counterfeiting or IP rights violations.

Although the DSA – which is the latest relevant and most recently enacted regulatory innovation –has accomplished an objective update of the previous body of law (among which the novelties on the subject of notice and takedown, and of the ‘stay down’ injunction instrumentation are both worth mentioning), it maintains some of the previous issues in the area of secondary liability of ISPs. This is despite the creation of a more regulated and controlling system operated by national authorities and the European commission. The Act also fails to regulate some digital services that are difficult to fit within the numerus clausos of the three traditional categories provided for ISPs themselves, that is, mere conduit, caching or hosting providers.

In order to understand the current critical issues in the system of combating online counterfeiting these considerations must be placed alongside the protection platforms and tools provided by service providers. These include, for example, those of the Alibaba Group and the Meta social networks. The initiatives taken by some of the major giants of online commerce, such as Amazon and eBay, also deserve mention.

Certain characteristics of such instruments should be highlighted that can make it complicated to execute appropriate protective initiatives. First and foremost, there is an absolute lack of procedural and usage uniformity of such platforms, even within the same membership group. During an infringement investigation and the subsequent online enforcement initiative, one often comes across clusters of infringements that are however present in different online marketplaces. Although these may fall under the same organisation, they provide for different (and sometimes questionable) methodologies for filing takedown petitions that must in fact be for the same infringement, although based on different titles (eg, exclusively national). This subdivision assumes that certain online marketplaces are defined and considered ‘local’, able to ship the possible infringing product exclusively in the country of reference. This is opposed to online marketplaces, which are defined as international (present in the same corporate group); for these it is possible to proceed with a takedown petition based on European and/or international titles, since it is assumed that only these platforms are accessible by non-local users.

A further critical issue, identified in some of the protection platforms used by the most reputable ISPs, consists in the requirement to indicate the country for which the IP title being claimed is being protected. This must coincide with the country of residence indicated in the account holder of the infringing post, that is, with a datum arbitrarily provided by the unauthorised party (and most often without any basis and, therefore, untrue). This is despite the fact that the e-commerce or social media of reference is international and, therefore, allows the non-genuine product to be advertised and distributed outside the country itself.

Such evidence denotes the presence of the unproven belief that criticality is territorially limited. Such a belief indicates a limited view of the current distribution channels of counterfeit products and prevents the appropriate protective steps from being taken.

Among other discrepancies found during online anti-counterfeiting activities over the years is the absence, in some IP rights protection platforms, of the possibility to submit requests for removal based on IP titles not included in the catalogue of protectable rights. This makes any request for removal in this sense (eg, designs and models) impracticable. In addition, although there may be clear evidence of the existence of a cluster of different individuals and companies engaging in blatant illegal conduct, requiring the immediate removal of all sales advertisements present online and traceable to the same individuals, these limitations make it impossible to perform a complete cleanup of the violations, making a partial protection action economically unjustified.

The cumbersomeness of some protection platforms, in the face of more complex criticalities, and the inability of private professionals to avail themselves of the so-called one-click removal procedures used by the players in the online brand protection services industry, may be a deterrent for small and medium-sized companies to activating a protection action. The overall cost may not justify the time taken to physically perform the anti-counterfeiting activity, or, as seen earlier, it may lead to only partially effective results.

Under the current and personal view of online anti-counterfeiting, the paradox is that the limitations and discrepancies mentioned above mean merely ‘quantitative’ protection activities can be carried out (eg, through the constant monitoring of hundreds of e-commerce sites and through the simultaneous removal of numerous illicit contents) and are, therefore, executable only by clients with a certain allocated budget. The results of these activities would be disconnected and qualitatively limited, making them unsuitable for reconstructing the real unauthorised supply chain and allowing counterfeiters to regenerate and reorganise their illicit distribution channels.

Although the current system provides several tools to fight online counterfeiting, the current scenario remains disconnected from the real dynamics and rapid evolution of the digital market. It does not tackle some of the major obstacles that prevent a profound fight against counterfeiting that starts from the online market from beginning. These include the existence of additional regulations in the current European and non-European legal landscape. Just some examples are the impossibility of identifying e-commerce counterfeiters, the absence of a system for controlling and certifying the sellers themselves, and the absence of an administrative authority or authorities that can implement sanctions against offenders.

The hope is to achieve an overall harmonisation of instrumentation (legal and otherwise) in fighting online counterfeiting that is accessible and attractive to all types of business, regardless of their size. Such a harmonisation would allow for decisive results, even in the online market – thus eliminating the critical issues posed by the counterfeit industry. These will continue to arise since, as in all competitive markets, as long as there is a demand there will be a supply (albeit in this case an illicit one) to satisfy it.

Endnotes

[1] EUIPO, World trade in counterfeit goods: 348 billion euros in value, press release April 18, 2021.

[2] Source: OECD and EUIPO (2021b) © Ministry of the Interior and Crime&tech - Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 2022; FATA Project: From awareness to action. Strengthening knowledge and public-private cooperation against new forms of online counterfeiting, Milan: Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore.

[3] Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry into the Phenomena of Counterfeiting, Commercial Piracy and Abusive Trade, Report on the Phenomenon of Web Counterfeiting, 23 March 2017, p. 20.

[4]https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnelweb/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/observatory/documents/reports/2023_IP_Tech_Watch_Discussion_Paper/2023_IP_Infringement_and_Enforcement_Tech_Watch_Discussion_Paper_FullR_en.pdf.

[5] European regulation approved on 09 December 2023 by the EU Commission, EU Council and EU Parliament and awaiting approval of the final text.

[6] Consider the case where an AI model is implemented through the use of source code available on open-source platforms. It should be noted, however, that many licenses defined as open source are also ‘copyleft’, i.e., modifiable by parties other than the original author, as long as the modified work retains the same legal regime. It is quite clear, therefore, that open source-copyleft code could contaminate newly developed code (which may be considered open-source code) creating problems from a legal point of view, as it could be used and/or modified freely and free of charge by third parties).