United States: Last 12 Months See New Court Precedents and Fresh Ways to Challenge Existing Registrations

This is an Insight article, written by a selected partner as part of WTR's co-published content. Read more on Insight

In summary

This chapter provides an overview of key developments in trademark litigation in the United States over the past year. It addresses new legal precedents set by the US Supreme Court, federal trial and appellate courts, and the US Patent and Trademark Office’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board. It also provides guidance and takeaways from the first wave of decisions interpreting the 2020 Trademark Modernization Act’s expungement and re-examination procedures.

Discussion points

- First Amendment defence and extraterritorial application of US trademark law

- Scope of trademark protection for virtual goods and burden of proof for ‘crowded field’ defences

- Importance of complying with formalities in USPTO forms

- Defences based on deficiencies in asserted trademark registrations

- Unique cancellation remedy available under the Pan American Convention

- Best practices in expungement and re-examination proceedings

Referenced in this article

- Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc v VIP Prods LLC

- Abitron Austria GmbH et al v Hetronic Int’l, Inc

- Hermès Int’l and Hermès of Paris, Inc v Rothschild

- Spireon, Inc v Flex Ltd

Injunctions at a glance

| Preliminary injunctions – are they available, how can they be obtained? | Available upon motion in court. Movant enjoys statutory presumption of irreparable harm upon showing likelihood of success on the merits. |

| Permanent injunctions – are they available, how can they be obtained? | Available after prevailing on the merits in court. Movant enjoys statutory presumption of irreparable harm upon a finding of infringement. |

| Is payment of a security/deposit necessary to secure an injunction? | Security is required by rule to perfect a preliminary injunction, but the amount is discretionary. Security is not needed for a permanent injunction. |

| What border measures are available to back up injunctions? | Registered trademarks can be recorded with US Customs and Border Protection, a federal agency that will seize, detain and ultimately destroy infringing and counterfeit goods intended for entry into the United States. |

Introduction

Litigation regarding trademark rights in the United States typically occurs in federal courts or at the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) of the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). While the TTAB only has jurisdiction over disputes regarding federal registration, courts are authorised to address both registration and use in commerce. Meanwhile, pursuant to the 2020 Trademark Modernization Act, it is possible to petition the USPTO to re-examine existing registrations based on allegations of non-use. Recent decisions in all of these fora shed light on the scope of litigants’ rights under the US Trademark Act (15 USC §§ 1051 et seq., colloquially known as the Lanham Act), which governs federal trademark rights in the United States. In addition, these tribunals have clarified some of the more obscure procedural niceties of which litigants should be aware before initiating proceedings.

Guidance from US Supreme Court

Free speech rights do not always trump trademark rights

In the United States, trademark infringement defendants can assert that their use of another’s trademark is protected as free speech under the First Amendment to the US Constitution. While not universally applicable, this defence often arises when a mark is used in an artistic work. In such cases, the defendant argues that its use was merely creative expression and not for commercial purposes.

The US Supreme Court recently made it more difficult for defendants to prevail on First Amendment grounds. In Jack Daniel’s Properties Inc v VIP Prods, Inc, the Court unanimously rejected an appellate court’s opinion that a dog toy mimicking a bottle of JACK DANIEL’S-branded whiskey should be protected as a parody under the First Amendment, finding that the right to free expression does not excuse “trademark law’s cardinal sin” – that is, the use of another’s trademark “as a trademark”.

At issue was application of the so-called Rogers test, which evolved out of the 1989 decision in Rogers v Grimaldi. Unlike the traditional multi-factor test for likely confusion, the Rogers test weighs just two factors: (1) the accused work’s artistic relevance; and (2) whether use of the other party’s mark “explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work”.

The Court held that Rogers does not apply “when an alleged infringer uses a trademark in the way the Lanham Act most cares about: as a designation of source for the infringer’s own goods”. It returned the case to the district court to evaluate infringement under the proper standard.

After Jack Daniel’s, lower courts are less likely to apply the Rogers test, so limiting the First Amendment defence.

US trademark law does not govern infringement occurring abroad

The US Supreme Court has restricted application of the Lanham Act to cases involving infringing activity occurring within the United States. Previously, lower courts had interpreted the statute as authorising injunctive relief and damage awards related to any activity that had a ‘substantial effect’ on US commerce, even if that activity had occurred entirely abroad.

This issue arose in Abitron Austria GmbH et al v Hetronic Int’l, Inc, after the US-based manufacturer Hetronic sued its former EU distributor for infringing trademarks and trade dress associated with authentic Hetronic products. Even though 97% of Abitron’s sales occurred outside the United States, a jury awarded Hetronic more than $115 million in damages, $96 million of which related to Lanham Act violations mostly arising from non-US sales, and the district court granted Hetronic a worldwide injunction against Abitron. On appeal, the appellate court tailored the injunction to apply only to markets where Hetronic was actually selling products but upheld the damages award, reasoning that even activity occurring abroad had a ‘substantial effect’ on US commerce.

At oral argument, the parties presented various interpretations of the Supreme Court’s 1952 decision in Steele v Bulova Watch Co, the original pronouncement on the Lanham Act’s “sweeping reach” into other geographic territories. The Court’s majority opinion ultimately sidestepped Steele altogether, relying instead on a “longstanding principle of American law” referred to as the “presumption against extraterritoriality”. The Court found that the Lanham Act was not meant to be applied extraterritorially and could only properly be applied to govern infringing activity that occurred through use of a mark in commerce in the United States. Future cases will map out what specific types of use in commerce are actionable under the statute.

In the wake of Abitron, US-based litigants can no longer rely on US trademark rights to obtain relief against foreign defendants unless those defendants are using infringing marks in the United States. Because trademark owners will be forced to take a piecemeal approach to enforcement, jurisdiction by jurisdiction, they should evaluate and ensure that they have proper protection in all relevant jurisdictions worldwide.

Guidance from lower courts

Trademarks for physical goods sufficient to enforce in virtual environments

A battle over unauthorised use of the BIRKIN trademark and trade dress in the design of Hermès International’s famed BIRKIN handbag has garnered attention as one of the first cases to address the application of US trademark law in digital environments. Hermès, asserting registrations associated with its physical handbags, was able to obtain more than $130,000 in damages and a permanent injunction against the artist Mason Rothschild to stop him from selling digital images of ‘Metabirkins’ authenticated by non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

Rothschild argued that his ‘Metabirkins’ should be protected as artistic expression under the First Amendment of the US Constitution. As such, Rothschild asserted that the court should apply the Rogers test rather than the traditional, more stringent likelihood of confusion factors applicable in most infringement cases.

The district court agreed, but even under Rogers, a jury found Rothschild liable for trademark infringement, dilution and cybersquatting. Rothschild is appealing, although he himself has admitted that the distinction between real-life goods and virtual versions is “getting a little bit blurred now because we have this new outlet, which is the metaverse, to showcase . . . them in our virtual worlds, and even just show them online”. In other words, consumers recognise that many big-name brands are entering the virtual goods market, so in many cases brand owners may be able to rely on their rights vis-à-vis physical goods to prove confusion with virtual counterparts.

Opposer has burden to refute conceptual weakness defence

The Federal Circuit has decided that in TTAB proceedings where the strength of an opposer’s mark is in question based on third-party marks cited by the applicant/defendant, the opposer – not the applicant that raised the issue – has the burden of proving those third-party marks are not actually in use.

The applicant in Spireon, Inc v Flex Ltd sought to defend against an opposition to registration of the mark FL FLEX by arguing that the opposer’s cited marks FLEX, FLEX & Design, and FLEX PULSE were conceptually weak based on 30 third-party registrations and applications for other FLEX-formative marks. The applicant relied on Federal Circuit precedent establishing that “extensive evidence of third-party use and registrations is ‘powerful on its face’” to show that consumers have been accustomed to distinguishing between marks containing a common element. In the face of such third-party evidence, an opposer’s mark can be considered conceptually weak and thus not entitled to a wide swath of protection. However, the cited third-party marks must be in use to support a finding that consumers actually encounter them in the marketplace.

The Federal Circuit held that once the applicant introduced evidence of third-party registrations to demonstrate weakness, it was the opposer’s burden to show non-use of those marks. The court declined to address “the broader question of which party bears the burden of establishing non-use as a general matter”. However, the decision provides clear guidance on the burden of proof regarding the so-called “crowded field” defence in opposition and cancellation proceedings before the TTAB.

Importance of the ‘Domestic Representative’ field in US trademark applications

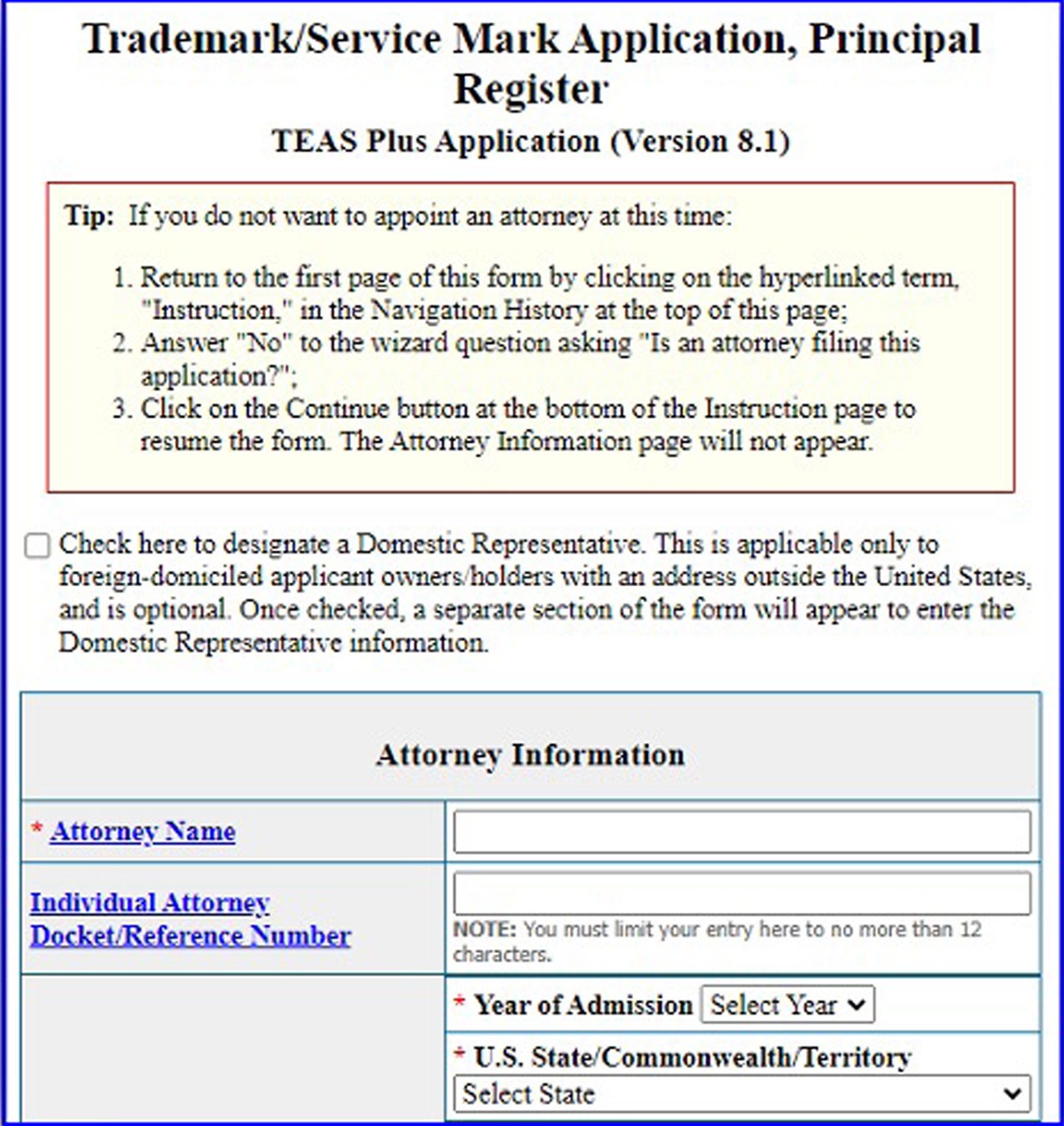

The USPTO provides non-US domiciled trademark applicants with an easy to overlook option to designate a ‘Domestic Representative’, as pictured below:

Figure 1

Source: USPTO

The form does not explain that, pursuant to 15 USC § 1051(e), the Domestic Representative is the appointed recipient of “notices or process in proceedings affecting the mark”, including service of process in a federal lawsuit. If no such representative is appointed, papers can be served on the applicant by serving the Director of the USPTO, who will then send the papers to the applicant’s address of record. In that case, the applicant might find itself party to litigation without actually having been personally served, as typically required under federal procedural rules.

This scenario played out in San Antonio Winery, Inc v Jianxing Micarose Trade Co with severe consequences. The court held that 15 USC § 1051(e) applied to service of process in court proceedings as well as USPTO proceedings, and thus the Director’s mailing of the complaint constituted sufficient service – even if the applicant did not have actual notice of the proceeding. The court further held that the statute does not conflict with the Hague Service Convention because the papers were served domestically and not in another country. Following the decision, the district court entered default against the applicant and a permanent injunction.

The same rule applied in Equibal, Inc v 365 Sun LLC, where a foreign applicant had designated US attorneys as counsel in connection with its application, but had not checked the box to formally appoint them as Domestic Representatives for the purpose of service. When the attorneys said they were not authorised to accept service of court papers, the plaintiff served the Director of the USPTO. The court found that such service did not conflict with either the Hague Convention or the Inter-American Convention, further illustrating the importance of the ‘Domestic Representative’ field in US trademark applications.

Guidance from the TTAB

Importance of ESTTA cover sheets in oppositions to Madrid Protocol applications

In Sterling Computers Corp v IBM Corp, IBM sought to extend its French registrations of STERLING and IBM STERLING to the United States pursuant to the Madrid Protocol. Sterling opposed based on the likelihood of confusion with prior-used marks. Its notice of opposition cited pending use-based applications for STERLING and STERLING & Design, common law rights in those marks, and common law rights in STERLING COMPUTERS. However, when completing the cover sheet form for filing through the TTAB’s Electronic System for Trademark Trials and Appeals (ESTTA), Sterling listed common law rights in STERLING COMPUTERS and the two applications, but not its common law rights in the two applied-for marks.

ESTTA cover sheets include fillable boxes for the identification of the applications, registrations and common law rights asserted. Although many opposers view the form as a ministerial formality, Sterling highlights the fact that an ESTTA cover sheet plays a very important role in Madrid Protocol proceedings. When a US opposition is reported to the International Bureau, it is the ESTTA cover sheet that is sent to the Bureau, not the underlying notice of opposition. Because the Madrid Protocol prohibits the amendment of an opposition to include rights or claims not asserted in the original filing, an opposer’s claims are limited to those found on the first-filed ESTTA cover sheet.

After the TTAB allowed Sterling to file an amended pleading to clarify its original allegations, IBM argued that Sterling should not be allowed to include its common law rights in STERLING and STERLING & Design in its amended pleading, because those rights were not expressly listed on Sterling’s original cover sheet. But the Board concluded that listing use-based applications (as opposed to intent-to-use applications) for the marks in question provided sufficient notice of reliance on the common law rights underlying those applications. In other cases, however, litigants may not be as fortunate. Therefore, it is important to pay close attention to both the substance of a notice of opposition as well as the ESTTA cover sheet in Madrid Protocol proceedings.

Failure to launch affirmative attack on cited registrations may result in waiver of key defences

A defendant in a TTAB proceeding cannot defend itself based on alleged defects in an asserted application or registration without affirmatively opposing the application or seeking to cancel the registration. The applicant in Nkanginieme v Appleton learnt this the hard way. The owner of a registration for NNENNA LOVETTE for “Product design and development in the field of . . . handbags” challenged an application to register LOVETTE for handbags. The opposer had waited to file its application for NNENNA LOVETTE until five months after the opposed application was filed, and just two weeks prior to initiating the opposition proceeding. The application matured to registration 14 months later, while the proceeding was pending.

The applicant argued that it had priority over the registrant based on its prior use and filing date, but the Board disagreed. The Board took the language of Section 2(d) of the Lanham Act at face value, concluding that where “a mark registered in the Patent and Trademark Office” is asserted in support of an opposition, there is no issue as to priority. If the applicant had wanted to challenge priority, it should have either opposed the NNENNA LOVETTE application or counterclaimed for cancellation. The Board held further that an applicant could avoid admitting likely confusion by alleging that:

there is no likelihood of confusion between the marks such that the opposition should be dismissed, or that if there is a likelihood of confusion that Applicant has actual priority and so Opposer’s registration must fail.

In other words, a defendant can attack an asserted registration without conceding confusion. Failure to do so may waive questions of priority.

Pan American Convention supports cancellation based on rights obtained abroad

Parties domiciled in the contracting countries of the 1929 Pan American Convention (Convention) – Columbia, Cuba, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and the United States – have a unique remedy available to them. Mark owners can challenge registration in one country based on prior rights in another of those countries.

The TTAB’s decision in Empresa Cubana v General Cigar Co highlights this unique procedure. In this case, Cubatabaco successfully cancelled General Cigar’s two registrations of COHIBA in the United States based on Article 8 of the Convention. Article 8 applies in cases where an application to register a mark in a contracting country is refused on the basis of a prior registration in that country. The applicant may seek to cancel the blocking registration using a prior registration obtained in another contracting country if either: (1) the owner of the blocking registration had knowledge of the petitioner’s prior use or registration in another contracting country; or (2) the petitioner has used its mark in the country in which it seeks cancellation.

Cubatabaco had previously registered its COHIBA mark in Cuba. The USPTO refused its applications based on General Cigar’s existing US registrations. But Cubatabaco prevailed on a petition to cancel General Cigar’s blocking registrations. It demonstrated, through General Cigar’s own records, that General Cigar was aware of Cubatabaco’s mark prior to filing its first application to register COHIBA in the United States and presented evidence from which that knowledge could be inferred. General Cigar has appealed. Nonetheless, the Empresa Cubana case serves as an important reminder of remedies available to trademark owners in contracting Convention countries.

Best practices in expungement and re-examination proceedings

The Trademark Modernization Act of 2020 created two new procedures to challenge existing trademark registrations based on non-use: expungement (15 USC § 1066a) and re-examination (15 USC § 1066b). By the end of 2023, almost 2,000 petitions to revisit ex parte examination of registered marks had been filed, but fewer than 5% resulted in either partial or complete cancellation. Each petition is reviewed prior to a proceeding being instituted, and many petitions are rejected as inadequate. While certain deficiencies might be curable, final rejections are not appealable.

To avoid rejection, petitioners should first ensure that they meet the relevant timing standards. Expungement petitions may be filed against registrations based on use, non-US registrations or the Madrid Protocol. They must be filed between the third and 10th years of registration if a mark is alleged to have never been used in interstate commerce.[1] Meanwhile, re-examination petitions may be filed up to five years after registration if a mark was not used as of the filing date of a use-based application or, in the case of an intent-to-use application, as of the date an amendment to allege use was filed or the end of the period in which a statement of use was filed.

Petitions must be supported by a verified statement outlining the nature and scope of petitioner’s search – either by petitioner or a third-party investigator – for use of the specific mark for the identified goods or services during the relevant period. Because such investigations must be tailored to the sales channels for the goods or services at issue, petitions have been rejected when based solely on searches of only one search engine, or investigations of just the largest online sales platforms.

The verified statement should be supplemented with clear, legible evidence of non-use. Potential sources of probative evidence are set forth in 37 CFR § 2.91(d)(2). These include but are not limited to trademark records, website printouts, filings from regulatory agencies, prior litigation filings, falsified specimens and/or other evidence of the registrant’s activities (or lack thereof) in the marketplace. Each practitioner has a duty of candour (37 CFR § 11.303(d)) that requires the disclosure of evidence undercutting a petition.

Following these best practices will reduce the likelihood of rejection by the USPTO and increase the chances of a successful petition for expungement or re-examination.

Footnotes

[1] Until 27 December 2023, the 10th-year limitation does not apply, and expungement may be requested for any registration at least three years old.