India: High court jurisdiction questions set to reshape IP litigation

This is an Insight article, written by a selected partner as part of WTR's co-published content. Read more on Insight

In summary

This article explores intellectual property cases before Indian courts and recent interpretations of the law on the subject.

Discussion points

- Legislative framework

- Recent case law

Referenced in this article

- The Trade Marks Act 1999

- The Hershey Company v Dilip Kumar Bacha and Ors

- Dr Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd v Fast Cure Pharma

- The Tribunal Reforms Act 2021

- Girdhari Lal Gupta v K Gian Chaand Jain

- Dr Reddy’s Laboratories Limited & Anr v The Controller of Patents & Anr

Indian intellectual property law is rapidly evolving. Recent developments in intellectual property cases before the Indian courts have favoured a liberal approach, allowing right holders and businesses to effectively protect and enforce their IP rights in India. This includes setting up dedicated benches for IP cases in various high courts, the promulgation of rules towards expeditious disposals of such cases and procedures modelled to cater to unique situations arising in IP disputes. Indian courts have taken significant steps in setting up robust mechanisms to facilitate, in some jurisdictions even mandating, online filings. With the Supreme Court of India live-streaming important cases, Indian courts have set up infrastructure enabling and even facilitating virtual court hearings. While these developments have reshaped litigation in the recent times, the changes have also given rise to contentious issues. One such issue that has recently been discussed pertains to the jurisdiction of various high courts while dealing with rectification petitions in trademark cases.

In 2024, there have been significant developments in the legal interpretation of the jurisdiction of high courts in India for handling trademark rectification cases under The Trade Marks Act 1999.

Legislative framework

The Trade Marks Act 1999 governs trademark law in India. It succeeded the Trade Marks and Merchandise Act 1958, and has been in force since September 2003. In India, a suit may be instituted where a defendant resides or works for gain, or a cause of action arises. The Indian courts, have given, rightfully so, an expansive interpretation to where ‘the cause of action, wholly or in part, arises’. Thus, it has come to include the transactions and infractions occurring even in the virtual domain and online, provided a website is interactive in nature and effectively targets users of the particular jurisdiction.[1]

Furthermore, trademark and copyright law allows a right holder an additional venue for instituting a suit for infringement of its rights under the respective statutes, which includes the place of the plaintiff’s residence or business. This conferment of additional forum of jurisdiction has materialised into a catena of case law that limit the extent to which a right holder may take benefit of the provisions.[2]

While some courts have interpreted the jurisdiction to hear rectification petitions as being any high court, others may have based it on general principles of jurisdiction. These principles may include the nature of the proceedings, the place of residence, the carrying on of business or the cause of action. However, with the changing times, courts are in favour of interpretations that rely on the dynamic effect of legislation. This means that the high court would have jurisdiction if the effect of the registration is felt within its territorial jurisdiction.

A recent controversy in the domain of jurisdiction exercisable under The Trade Marks Act 1999 revolves around the institution of rectification petitions[3] (seeking the rectification or correction of registered trademarks). Two judgments of the Delhi High Court clashed on the subject – The Hershey Company v Dilip Kumar Bacha and Ors[4] (Hershey) and Dr Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd v Fast Cure Pharma[5] (Fast Cure) – and the issue was referred to a larger bench.

A rectification petition, until 2021, could have been preferred before the registrar or an erstwhile appellate tribunal, known as the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB). The Act and the concerned rules posit the following practices:

- the Trade Marks Registry has five offices located in Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Kolkata, New Delhi and Chennai, with the territorial jurisdiction of the appropriate office of the Trade Marks Registry divided among them;[6]

- the Trade Mark Rules[7] define the appropriate office of the Trade Marks Registry based on the territorial location of, inter alia, the principal place of business or place of business of the applicant of the trademark; and

- the appropriate office of the Trade Marks Registry is also the venue for rectification petitions.

Interestingly, the IPAB would preside as a circuit bench, which means that the same bench would preside over the jurisdiction of the five offices of the Trade Marks Registry.

Thus, a prospective petitioner could invoke the jurisdiction of the registrar (at the appropriate office of the Trade Marks Registry) or the IPAB.

If a petitioner approaches the IPAB, the IPAB would adjudicate the rectification petition in the jurisdiction of the appropriate office of the Trade Marks Registry. Therefore, the subject order or proceedings would be under the purview of the respective high court of the jurisdiction of the appropriate office.

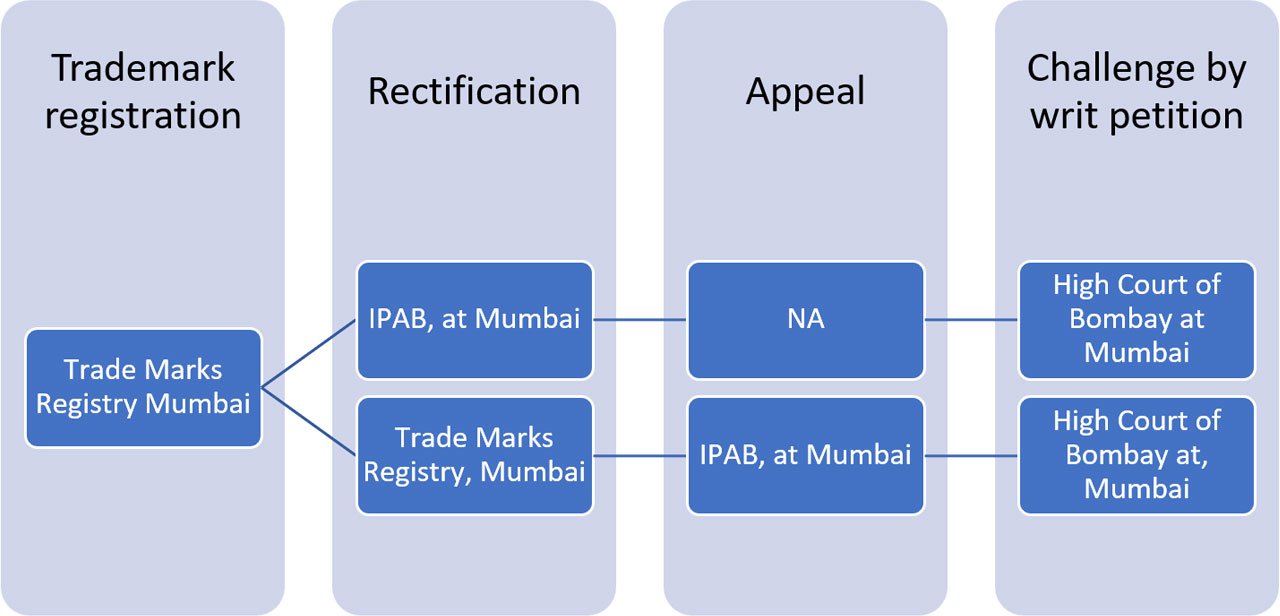

To better illustrate this, Figure 1 demonstrates a trademark registered with the Trade Marks Registry in Mumbai.

Figure 1.

However, with the passing of the Tribunal Reforms Act 2021, IPAB was abolished, and rectification proceedings under The Trade Marks Act 1999 now lie before the high court. The roots of the controversy in discussion can be found in the absence of a definition of ‘high court’ in the Act.

Recent case law

Before delving into the cases under scrutiny, a side note to discuss Girdhari Lal Gupta v K Gian Chaand Jain[8] (Girdhari Lal) and Dr Reddy’s Laboratories Limited & Anr v The Controller of Patents & Anr[9] (Reddy’s) would prove to be instructive.

Girdhari Lal was a seminal three-judge full bench decision, which laid the foundation for recent orders of the Delhi High Court that this article intends to explore.

The Girdhari Lal judgment addressed a similar question of jurisdiction under the then prevailing Designs Act 1911 (as amended in 1970). The Designs Act 1911 was earlier the Patents and Designs Act 1911 and governed Indian patent and design laws. In 1972, with the Patents Act 1970 coming into effect, the statute was amended and it came to be the solitary act governing design law in India. The amended Act’s section 51A postulated a cancellation of design registration before the high court. The Act also defined the term ‘high court’ to refer to the high court of that territorial state. In Girdhari Lal, the Court was called upon to examine which high court or high courts would have the jurisdiction to entertain the cancellation petition. The key submission that the Court addressed was that the subject matter of a design registration, and its consequent cancellation petition, would arise where the design registration was granted. The Court recognised and agreed that the ‘static effect’ of such registration would accrue jurisdiction in favour of the high court within whose local limit the registration was granted. However, the Court further recognised that such a registration entails a ‘dynamic effect’, as the impact of the registration of such registered design extends across India and travels beyond the place of registration.[10] As the dynamic effect of the registration can be felt by persons who may be using the design, the high court of the place where the aggrieved person resides or where the alleged legal injury is said to have taken place would also have jurisdiction. In arriving at its conclusion, the Court also took note of the use of the definite article ‘the’ preceding the term ‘High Court’ in section 51A, as one indication of the legislative intention to confer jurisdiction on the high court within the territory of which subject matter has the necessary nexus.[11]

This position was consistently adopted in the Reddy’s decision, which addressed the question of jurisdiction in respect of revocation petitions under patents law, post-abolition of the IPAB. This was primarily because the Patents Act 1970 succeeded the Patents and Designs Act 1911, and the legislative intent, as interpreted in Girdhari Lal would squarely apply to the current Patents Act. Furthermore, it had a similar ambiguity regarding the definition of ‘high court’. Relying upon Girdhari Lal, the Reddy’s decision laid down the following as to which places the cause of action in such a situation could arise:

- where the patent application is filed or granted;

- where the manufacturing facility of a person interested is located or where the approval for manufacture or sale of product has been granted, but the same is prevented due to the existence of the patent;

- where a cease and desist notice may be served or replied to from or where the suit for infringement has been filed;

- where patentee resides or carries on business (ie, manufactures or sells the patented invention);

- where the import of the product may be interdicted due to the existence of the patent or where the export of product is being stopped due to existence of the patent; and

- where research on a commercial scale in respect of the patented subject matter is curtailed.

In the background of the Girdhari Lal and Reddy’s decisions, in Fast Cure, the Court was presented with the opportunity to discuss the issue in respect of rectification petitions under The Trade Marks Act 1999. The Court in Fast Cure disagreed with the restriction proposed, that the term ‘high court’ would be restricted to the high court within whose jurisdiction the Trade Mark Office, which granted registration to the impugned mark, is situated. Acknowledging that if the rectification were to be preferred before the Trade Marks Registry, it ought to be the Registry that granted the registration, the Court relied upon Girdhari Lal and held as follows:

36.3. Thus, though the Registrar, who could exercise jurisdiction under Section 47 or Section 57 would undoubtedly be the Registrar who granted registration to the impugned mark, the High Court which could exercise such jurisdiction would not only be the High Court having territorial dominion over such Registrar, but also any High Court within whose jurisdiction the petitioner experiences the dynamic effect of the registration.[12]

Rival contentions had laid considerable emphasis on the legislative history of The Trade Marks Act 1999. The preceding enactment (the Trade Marks and Merchandise Act 1958) had extensively defined the term ‘high court’ to the extent that it espoused a complete section[13] to identify ‘the High Court having jurisdiction under this Act’. The original Trade Marks Act 1999 did not find any requirement for defining ‘high court’ considering the jurisdiction was sought to be vested in favour of the IPAB. Again, with the Tribunal Reforms Act 2021, the legislature did not introduce any amendment in The Trade Marks Act 1999 to offer any definition to the same. This noticeable absence is what the Court considers to be the legislative intent of not restricting the rectification petitions before any particular high court, or more particularly, the high court within whose jurisdiction the registration has been granted.

In the Hershey decision, the Delhi High Court disagreed with the Fast Cure decision, which stressed the position as prevailing prior to the current Trade Marks Act and under the earlier Act of 1958. In Habeeb Ahmad v Registrar of Trademarks, Madras,[14] which in turn relied on Chunulal v GS Muthiah,[15] when addressing rectifications under the Act of 1958, the Court held that the high court with the jurisdiction to exercise power in relation to cancellation and rectification petitions, as well as appeals, would be the high court within whose jurisdiction the application for trademark registration was filed.

In the absence of any definition of ‘high court’, the lead judge considered the approach undertaken in Fast Cure to be expanding the scope beyond the explicit provisions.[16] The Court further stressed that the Girdhari Lal and Reddy’s decisions were based on the same statutes that were in contrast to The Trade Marks Act 1999 being discussed in the Fast Cure case. The suggested ‘dynamic effect’ of trademark registration was not one conceived of under the Act of 1999 and, therefore, the reliance on Girdhari Lal was not appropriate.

The issue is now pending consideration before a bench of five judges of the Delhi High Court, and the outcome would certainly have far-reaching effects.

Conclusion

In the current landscape, the ease of doing business in India and the prominence of digital transactions and websites has led the courts to adopt a progressive judicial approach while interpreting several facets, including jurisdictions in trademark enforcement cases. Based on the same, a reading of the tea leaves would suggest that the five-judge bench is likely to adopt a similar interpretation in respect of such rectification petitions.

The expansive interpretation of ‘cause of action’ already provides a window in favour of the plaintiff to invoke jurisdiction of a forum convenient to the party.

One may argue that as per the trite principle of forum conveniens, appropriate forum, is one that suits the plaintiff. While prioritising the same, it is vital that the court closely examines each case to ward off any abuse of such privilege available to the plaintiff. In fact, courts will also have to consider situations where a suit for infringement is pending in one court and another becomes the venue for the rectification, concerning the same parties and issues. This may result in multiplicity of proceedings.

Alarm in this regard is expressly noted in the Fast Cure decision. Couched in the principle of dominus litus, it was advanced that if the law had permitted recourse to several forums, the litigant was at liberty to choose the platform that was most inconvenient to the opponent.[17] The Court’s reasoning rejecting the contention is worth emphasising:

Litigation may be adversarial, but cannot be oppressive. It cannot be made a means of harassment. The aim of litigation is not to secure a victory come what may, but to secure the ends of justice. Justice is our sanctified preambular law; not even law, and law which does not aspire to justice is not worth its name. Use of the law in an unjust fashion, even if the strict letter of the law permits it, is not use, but misuse and, perhaps, in a given case, even abuse.[18]

This cautionary note is not out of place. In the attempt to enable ease of enforcement, steps must be in place to stem exploitation or abuse of the process. The provision for additional forum for enforcement of rights, as one under The Trade Marks Act, is unique to commercial disputes. Its exercise must be carefully considered and examined. Therefore, a more rigorous assessment of jurisdiction by the court, at early stages of suit proceedings, would, perhaps, discourage abusive filings. This could be in the form of a preliminary hearing by the court to assess maintainability of suits. Further, a flexible and frequent adoption of summary judgment by the courts would also aid in addressing the credibility of challenges to jurisdiction. Statutes must also keep evolving to tackle new forms of transactions and conducting business. With the Indian courts embracing virtual hearings and online filings, we have taken significant strides in enabling accessibility for the litigants. Thus, possibilities remain varied, with the correct match to be ascertained.

Endnotes

[1] Banyan Tree Holding (P) Limited v A Murali Krishna Reddy & Anr, 2009 SCC OnLine Del 3780.

[2] Indian Performing Rights Society Limited v Sanjay Dalia, (2015) 10 SCC 161,

Ultra Home Construction Pvt Ltd v Purushottam Kumar Chaubey & Ors, (2016) 65 PTC 469 (DB);

Manugraph India Limited v Simarq Technologies Pvt Ltd, AIR 2016 Bom 217

[3] Section 47, 57.

[4] Hershey Company v Dilip Kumar Bacha, 2023 SCC OnLine Del 3914.

[5] Dr Reddys Laboratories Ltd v Fast Cure Pharma, 2023 SCC OnLine 4953.

[7] 2002 and 2017.

[8] Girdhari Lal Gupta v K Gian Chand Jain, AIR 1978 Del 146.

[9] Dr Reddy’s Laboratories Limited & Anr v The Controller of Patents & Anr, 2022 SCC OnLine Del 3747.

[10] Girdhari Lal, para 10.

[11] Girdhari Lal, para 21.

[12] Fast Cure, para 36.3.

[13] Section 3 of the Trade Marks and Merchandise Act 1958.

[14] MANU/AP/0093/1966: AIR 1966 AP. 102.

[15] MANU/TN/0211/1959: AIR 1959 Mad. 359.

[16] Hersheys, para 51(iii).

[17] Fast Cure, para 30.11.

[18] Fast Cure, para 30.12.